Echoes of Redemption: From Bondage to Brothers

Those Things that Bind Us

Today, I want to share a story about a young man. It’s a real person and a real story, not something somebody made up.

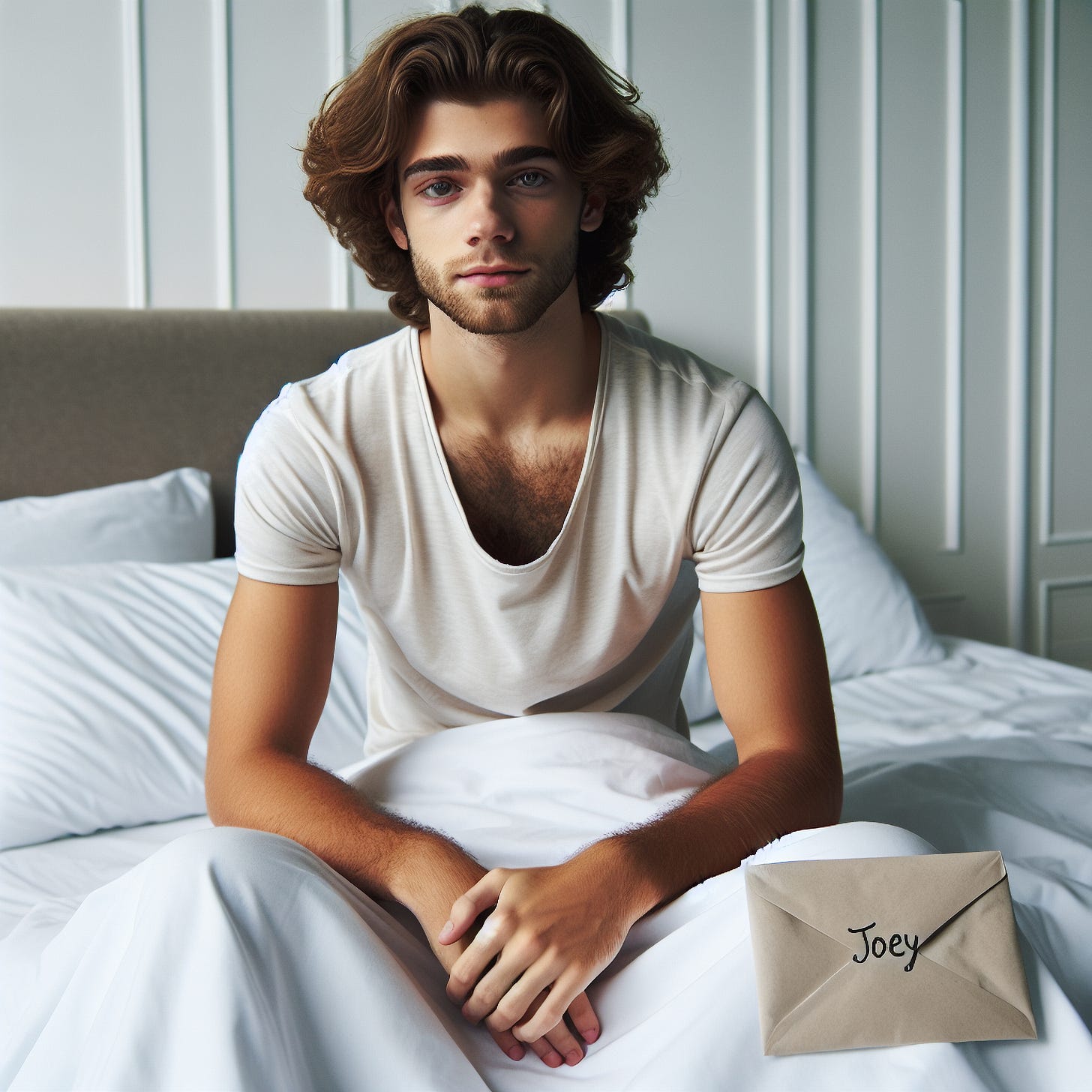

But, just to be safe, let’s call him Joey.

Joey had it all.

Well, not all, but everything he needed. His family wasn’t super-rich or anything, but he had everything one could responsibly hope for in life, beginning with two parents who loved him well. His parents did all the things people say good parents do, including take him to church where Joey served as an altar boy.

Now, don’t get ahead of me. The story is going to take a turn in a moment, but don’t let recent stories about sexual abuse in the Catholic Church give you any ideas about what’s to come. That wasn’t the problem.

Truth be told, there weren’t any problems. Except for one experience Joey had as a toddler.

He contracted hepatitis.

His parents did their best to care for him until they were finally forced to take him to the hospital. He was admitted, and they had to leave him there for an extended period of time.

Little Joey was confused when his parents left him there with strangers. Everywhere he looked he was surrounded by the coldness of bright white. The walls, the clothing of the medical staff, his sheets, and the frigid metal bars of the crib which was akin to a prison cell for the duration of his stay. His parents would come to be with him during the day but would have to leave him in the evening.

It was a lot for a 2-year-old. He clung to the bars, helpless to find the warmth of interactive love his parents provided at home.

The feeling of abandonment made an impression on him at that young age. As he grew, the memories lingered and perhaps became a subconscious, driving force for years to come. He’d grow to be an outgoing kid and being with others who reciprocated affection provided a particular safety.

In what some might consider a “coming of age” experience, Joey found himself in a social situation where friends offered him his first drag on a joint. He went along, with a subconscious that was far more concerned with disappointing his group of friends than it was developing a drug habit. Besides, it was only marijuana. The combination of the social acceptance and the psychological effect Joe experienced from a puff of the magic dragon was soothing. The anxiety of being left alone would disappear, and taking drugs with friends, often providing the drugs himself would ensure the friends stuck around. Soon, he was trying other drugs, stronger with deeper highs.

He found if he had drugs, his friends were nearby.

It was not long before Joey developed a habit, and the habit turned into dependence. You might say Joey was in a constant high for the last three years of high school. If he came across money, it went to feed the strengthening addiction.

The summer after his senior year in high school Joey and his friends heard about a music festival in upstate New York. The festival was going to celebrate love and peace, and the people there were going to celebrate each other and the world they lived in, hoping for peace in the future.

That might have happened, but it’s not what Joey remembers. He remembers Woodstock as a muddy cesspool of humanity without enough food or bathroom facilities. And he has vague memories about warnings not to take the brown (…or was it the red?…) acid. It didn’t matter. He was high for the entire experience, which somehow felt more like a low.

Later that summer, after he spent his educational grants and scholarships on drugs, he and his friends decided to go to one more festival. It was a two week experience this time. Drugs pulsed through his bloodstream for the duration of the event during which he did not sleep.

Two weeks. No sleep.

Joey returned home, a physical and emotional train wreck. In a moment of depressive clarity he looked around and saw the mess, one he realized he’d created for himself. All he saw was a life squandered. High school was over, and friends were going separate ways. He was left with himself and the drugs, and without friends, well, they meant nothing.

Soon Joey found himself in a mental institution, placed there by a court order. You’d be right to assume there was more to the story about how he found himself in court, but for the sake of brevity we’ll leave those details for another time.

Surrounded by mental illness of the most extreme, once again in a hospital cordoned off from the people he cared about. Joey was done with life as he knew it, ready to be healthy or die, the latter seeming more likely and perhaps more appealing. The steps towards health were sterile, almost dehumanizing interactions with the people at the hospital around him. The worst interactions were with a roommate who tried to kill himself by eating his own feces. This was not helpful and certainly did not bring him to an emotional state conducive for healing.

For the most part, the medical staff wasn’t much better. Dressed in white to match the walls and ceilings of his prison, interactions were sterile, devoid of the warmth Joey so craved and needed. They provided medication, watched him to be sure he took it, and most interactions were obligatory in nature.

One day, as he stared out the window of his hospital room, he noticed a cross at the top of a steeple in the distance. Set against the deep blue of the morning sky the cross seemed to glow, shimmering in a way that transfixed him. In desperation, Joey said a quick prayer. Just one sentence, pleading for a miracle.

“God, you gotta help me!”

It was then that he began to notice someone on the staff that was different than the rest. An administrator named Mr. Handy.

Alfonso Handy was an administrator who oversaw the nuts and bolts operations of the ward to which Joey had been assigned. He’d assign patients to rooms as well as the scheduling for daily care personnel. He was the one in contact with families for admission, transfers, and releases, etc. He greased the cogs of the hospital’s machinery. His job wasn’t treatment of patients, strictly speaking, and it would have been easy to take a hands-off approach and avoid personal interest in patients. But that wasn’t how Mr. Handy operated.

He took notice of Joey, and saw something. Almost immediately he took to the young man. As he ensured Joey had his medications and was scheduled to meet with the right people, he’d also take time to pass along words of encouragement: “Joey, you don’t belong here.”

After Mr. Handy left his shift, Joey would find envelopes left for him here and there, pieces of encouragement left for him to find. Sometimes the envelopes contained only a note of encouragement. At other times it contained acrostic poems that offered promise for tomorrow.

Hope.

Mr. Handy was the one glimmer in the darkness—the sole individual who had a manner different than the rest.

Mr. Handy went further. He mailed letters to Joey’s parents telling them what a wonderful son they had, that they ought to hold on to their hope, and that he believed in Joey and knew he’d find victory.

Joey would find victory, and these days he points to Mr. Handy as the reason why. In a real way, Mr. Handy helped “Joey” graduate to Joe. He was the voice of support not condemnation, the one who pointed towards hope, not consequences. He reminded Joey, well…Joe, of his value, not his mistakes.

At his worst moment, when Joe saw his life at end, he found health and returned a new man because somebody saw his value when he couldn’t.

This made all the difference.

But, my friends, there is more to this story.

The More of the Story

The rest of the story is…complicated.

Not Joe’s part. Joe turned out just fine. Tremendous, actually! Without so much as a single relapse.

The fact is, while I’ve met Joe on multiple occasions, I know this story from his daughter and my good friend, Jes. We met in college in the mid-1990s. She dated and would eventually marry a friend of mine, Bob, who I’d grown up with. We’d grow closer as my wife, Joy, and I had children the same age as theirs. Jes would watch our children for a while, and our kids remain close to this day.

Even so, we had no idea our families had a connection that went all the way back to the 19th century. Maybe earlier. It involves a man who was once enslaved on the Delmarva Peninsula, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

I’ll explain.

Given the meaningful role Mr. Handy played in Joe’s recovery, his family always lauded him as the reason their family exists. He was the beacon of hope that made a turnaround possible for young Joey.

With Mr. Handy’s love in the back pocket of Joe’s heart, he’d get healthy, get a job, find love, have babies with his wife… yada, yada, yada… they lived happily ever after.

It wasn’t until 2020 that Jes finally saw a picture of Mr. Handy. This is when she learned he was African American. Through the years of the stories, she’d always pictured an Italian guy, someone like her and her family. Feeling a bit awkward about this discovery, she asked her dad to confirm.

“Dad … Mr. Handy was black?”

His answer was matter-of-fact. “Yeah. So?”

“You never told me that.”

“Well…” Joe thought for a second, then continued in his succinct, pragmatic tone. “It never mattered.”

Jes had to admit he was right. There was something refreshing about the fact that Mr. Handy’s skin color was a complete non-issue for her father. Not even a subject worth bringing up. In the story, one man cared about another young man and helped bring him back to health.

But still, something ate at her.

She wondered what the experience might have been like for Mr. Handy if the roles were reversed. What if he had been the addict. What if the black man had been the one who had made some bad decisions. Would the court have ordered him to a hospital for observation, or to a prison?

We won’t ever know the answer to this question because it’s not what happened, and we can only speculate.

Instead of speculate, Jes decided to do research on Mr. Handy and his family.

Whereas Jes and I had been somewhat close for a period of our lives, we’d mostly lost touch over the years. In 2016, our family had moved to a place called Salisbury, Maryland. And communications to or from her and her family were rare. So, the research I’d begun to do about my own family’s history of enslaving people had absolutely nothing to do with her. None.

Zilch.

My family had a couple bricks we’d always displayed in our house that we believed were made by enslaved people our ancestors owned. I’m not sure what to make about the fact that we displayed them. You may recall I’ve written about this before.

I was not only researching my family’s history, but also that of my wife’s. Just across the river from their home was a place called Pemberton Park, which was once known as Pemberton Plantation. There was a family tie to the property. My father-in-law was a descendant of the original owners of the property, the Handy family. And, as a plantation in the south, I knew this likely meant my wife’s family had an ancestral history of enslaving people as well.

I wanted to know more, to understand how things had played out over the years. I began to do some research of my own and I used the research as part of creating content for a podcast I was doing.

Everyone I asked about the history of black people on the Eastern Shore all pointed to one person, Dr. Clara Small. Dr. Small had dedicated her life to telling the story of the history of the black experience on the Eastern Shore. So I interviewed her, and wrote the most informative article you’ll find about her on the internet.

Jes was digging deep. She learned Mr. Handy and his family were the descendants of people who had been enslaved in Salisbury, Maryland. There had been a man named Carr Handy and that he’d been enslaved at a place called Pemberton Plantation. This is where the surname Handy came from, as enslaved people most often took the last name of their owners. An historian named Dr. Clara Small had written about him.

She googled Dr. Small. There were several returns. A news clip here, a video there. Dr. Small was well known. But then she clicked on an article, Delmarva’s Own Historian: Dr. Clara Small. The article accompanied a podcast about the Delmarva Penninsula, on which Dr. Small had been a guest. Comparatively speaking, it offered more information than anything else she’d found.

Wondering if she could find a way to contact Dr. Small herself, Jes looked to see who had authored it.

Wait…

No way…

She clicked on the podcast “About Us” page.

I was sitting at work when my phone buzzed on the desk in front of me. It was a text from my friend Jes, who I’d not heard from in several years.

“Jeff… we need to talk.”

There’s always more to the story…

The Unfiltered Scribe is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support independent writing, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Next week: The “faith” part.

WOW !! This is fascinating, looking forward to the next "chapter".

Thrilling to hear it in your voice.