My Family Enslaved People. Now What?

The Story of Two Bricks, Made by Slaves, and One Man's Journey Towards Answers and Reconciliation

If you’ve been following my work in February, then you’ve surely noticed my focus on my country’s historical record when it comes to slavery. This has been intentional. It’s Black History Month, and this is the part of the history I’ve focused on. I’ve suggested Reparations are a mandate for the Christian faith. I’ve shared two books, one which helped me understand the difficult intricacies about how chattel slavery built America, including the north, and another which shed some light on the challenges and outright white resistance black communities have had to overcome for equality.

This topic is important to me, and today I begin to share why.

The fact is, my family enslaved people. My ancestors owned other humans for the purpose of free labor, a means to serve their economic interests. People whose blood I share played a part in perpetuating a dark chapter in our country’s history. It’s a hard truth for me, one which demands reflection and acknowledgment.

For me, the story starts with two bricks that our family had sitting on the hearth when I was growing up. They’re bricks we believe were made by the enslaved people my family owned. These bricks drive a lot of what I write about, including the entirety of today’s post.

That said, on to the story…

Two Bricks, Made by Slaves

I don’t normally struggle with car sickness when I’m driving. But on a warm day in June 2020, I wasn’t feeling great. The roads were windy, rolling up and down. If I’d been 8-years-old and sitting in the backseat, I probably would have been enjoying the tickles the sudden rise and falls would have caused in my belly. But I wasn’t that 8-year-old boy. I was in the front seat, driving a car that didn’t belong to me, with an elderly passenger serving as my navigator.

Likely, it wasn’t the motion of the car making me sick to my stomach.

“Can you see it?” Jean asked.

Doing my best not to run off the unfamiliar road, I glanced in the direction she indicated. The trees and brush molded into one big blur. I couldn’t see anything that seemed worth pointing out.

She tapped the passenger-side window with her pointer finger. “The family plot is back there.”

I squinted and looked harder. As I did, things began to come into focus a bit more, but only just. I could see the depth of the tree-line didn’t exactly give way to a forest. There was a vast open space that began about 20 or so yards from the road we were on. Still, I couldn’t make out anything of note.

“I’m afraid I can’t see it.” I told her, hoping not to disappoint my navigator.

“I think it’s in that grove of trees back there,” Jean guessed.

Checking my review mirror to be sure I wouldn’t be in anyone’s way, I slowed the car to a crawl. Looking in the direction Jean had pointed, I could now see the open space behind the tree-line was what had once been a dense forest. But now, finding a way to look past the trees and brush next to us I saw acres upon acres of stumps, small underbrush, and broken tree limbs scattered here and there. Except… yes. Sitting in an elevated area was a grove of trees left standing in place in the midst of all the felled timber.

I began to perspire a bit, hands clammy and beads of sweat appearing on my temples. I realized it wasn’t car sickness. No. I felt like an unwelcome guest. It wasn’t Jean. She was wonderful. It was, well, I just felt like I was beginning to turn over stones some people wouldn’t want overturned.

“We can come back another time,” I tried, getting a bit nervous about potentially trespassing on somebody else’s property in gun-lover country. It was a silly notion. The fact was I lived 5 hours from this place. Jean wouldn’t have any of it. She was the epitome of a sweet, southern belle. Well into her 90’s she’d had decades of practice getting southern hospitality just right.

“Oh, just pull off up here.” She said, pointing off to the right of the two-lane road we were on. “There’s a road you can walk up if you’d like.” She said it in a way that disallowed any thought that I would not walk up the road. Of course I’d “like.” How could I refuse?

As I pulled onto the road she was pointing at, I immediately recognized it was the entrance to the timber company access road. There was only just enough room to park. Blocking my way was a locked gate, with a yellow sign that deepened the foreboding feeling that I was sticking my nose where it didn’t belong.

POSTED- Private Property…Hunting, fishing, trapping or trespassing for any reason is strictly forbidden. Trespassers will be prosecuted.

Super.

I’d seen signs like this dozens if not hundreds of times throughout my life. But this time … this time there was a certain amount of sinister poetry in the moment. The no trespassing sign was there to send a message to outsiders. “You don’t belong here. We don’t want you here. Go back where you came from. NO. HUNTING. HERE.”

I was indeed, hunting.

There I stood. A guy from the northeast, visiting Victoria, Virginia to see if my family had a history of owning slaves. I wanted to know if “we” had engaged in the practice of owning other people. This little forest foray was part of my journey of discovery. Hunting not for animals, but for answers. Beginning to wonder if my efforts might be predacious, I could hear the voices of protest.

Who’s this northern elite trying to dig up the sins of our past?

But Jean didn’t seem to care. Well, truth be told she didn’t know what I was up to. I hadn’t shared the motives for my visit. For all she knew I was just learning about family history.

“Walk up the road!” She instructed. Following her directions, I walked up the dirt road, rocks crunching beneath my feet in the otherwise quiet timberland. Juxtapositioned against the red dirt, the gray pee-gravel below my feet looked as awkward and out of place as I surely did. Clearly from somewhere else, it had been brought in to shore up the dirt road. But at least it was invited. I on the other hand, was not. I was sure I was about to be shot by some trigger-happy landowner. Nevertheless I pressed on, because disappointing Jean seemed to be a worse fate.

Even as I came close to where I thought the plot was supposed to be, I saw nothing. The forest shrouded it in, revealing the gravestones only as I drew closer, the family ghosts staring at me, wondering why I’d never visited before.

It was a small plot of graves camouflaged by the oaks which had grown up around them for decades. The fallen leaves of years gone by lay all around in various states of decomposition. There was a short, iron fence roughly three and a half feet high surrounding the plot. The top of the fence was lined with ornamental spikes which served the dual purpose of looking both fancy and menacing. Had I any desire to hop the fence, I’d have thought better about it.

I could have walked right in if I’d wanted to. The gate was broken, hanging in a crooked manner, and held closed only by an out-of-place bicycle lock with a chrome chain. It was awkward looking against the black iron fence. I had no intention of entering the plot. I could see everything I needed to from where I was standing.

Most of the grave stones were weathered and somewhat difficult to read. Years of wind and rain had taken their toll on the limestone. But they all remained in place, upright and straight.

I looked for the oldest stone there. It belonged to “Charles Madison Hardy” who lived from 1836 – 1921. Not far away was a second stone for Chaz. The second was a bit more formal looking, with a symbol like an iron cross with a wreath in it carved into the top. I’d later discover this was the symbol of The Daughters of the Confederacy. Also was an engraving:

CO G 9 CAL VA CAL (Company, 9th Virginia Calvary)

Confederate States Army

It was an interesting stop for me. I hadn’t expected to be able to view these graves. The fence was beginning to show signs of disrepair, but wasn’t as bad as it could have been. Interestingly, one of the grave markers was for a man who was buried in the family plot as recently as 2015. Jean would later tell me that cousin Keith’s dying wish was to be buried with his ancestor, the legacy of the Confederacy was important to him.

But as interesting as I found the gravestones, it didn’t answer my question- Did my ancestors own slaves?

I wasn’t sure what I was asking, exactly. I wasn’t even sure why it was important to me.

As I returned to the parked car I took a moment to turn and look at the No Trespassing sign. The message held a strange, poetic symmetry, its words pointing at my own quest for answers. It was as if I was digging for some dirt on people I never knew, whose descendants I barely knew, and on a legacy I wasn’t sure I wanted to know about.

But I did want to know. I’d wanted to know for a long time. Initially, my question was little more than curiosity.

Growing up, my mother decorated our home with antiques she’d pick up here and there. It was the stuff of America gone by. Sometimes these were items from our family’s past, and they were what we held most dear. Little trinkets mom might have played with as a kid, or perhaps a butter churn a grandparent had used decades ago. Looking at – or more so, holding – these items always felt like a tangible way for me to connect to our past.

For as long as I can remember, two artifacts sat on the hearth of our fireplace in each and every home we occupied throughout the years. They were rustic, though unspectacular bricks. The story as told to me was that these bricks had come from the land my ancestors owned and had been made by enslaved people.

As my father recounts the story, he and mom collected them when they were visiting the ol’ stomping grounds of my maternal grandmother – the very grounds where I stood that June 2020 morning, decades later.

These days Victoria, Virginia is a sleepy has-been of a back-woods community. It was once a railroad town that probably would never have been described as “bustling.” And now, with the need for the railroad all but gone, it’s the kind of place people move away from looking for work in more populated areas. The current population is less than 2,000 people.

On the trip my parent’s made decades ago, they’d stopped by what they knew to be ancestral property on mother’s side. Grandma had been Christine Hardy, and they were visiting the land of the Hardy’s.

They’d stopped by the site where the home once stood, long gone by then with a few piles of rubble here and there. That’s where dad picked up the bricks.

Two bricks, made by slaves.

That was all I ever really knew about them. They were placed on the hearths of our fireplaces throughout the years next to wooden butter churns and pots mom used on occasion to make Boston Baked Beans.

There they sat. Still, quiet and untouched. Except that I did touch them. Once when I was exploring them as a child, and then later with intent and curiosity.

It’s not hard to believe the bricks were hand made. They don’t look as crisp as the factory-made bricks upon which they sat, and one of them even had a slight indentation in it about the size of the tip of a finger – as if the craftsman made their mark for us to see years later.

I never look at that particular brick without taking time to place my own finger in the little indentation. It gives me a sense of connection. I’d imagine the person making it using their hand to compress the soft clay down into the form without a thought about the indentation from their finger. Having no idea that the mark they left on the brick would leave an impression on my conscience generations in the future. The fingerprint – if that’s what it is – is a tangible link to my family’s past, nefarious or not. I consider if perhaps this connection, this gentle whisper from a voice in the past, is what motivates me to seek answers.

If anybody asked about the bricks we’d tell them what we thought we knew. Nobody ever asked for more details. They were an interesting footnote in our home decor. Nothing more. A blip from the past we didn’t think had any effect on us in the modern day. We didn’t give them a lot of thought until it was time to downsize and… do whatever it is you do with two bricks possibly made by your ancestors’ slaves.

When my maternal grandparents died in the early 2000’s, my mother was shouldered with the painstaking process of sorting through their lives. When she was done she immediately began on her own estate to prevent my siblings and me from having to experience the same chore. She threw things away, sorted and stored some others, and distributed yet more to her children and grandchildren.

Eventually this meant we had to figure out what to do with the bricks.

I wanted them. I couldn’t bring myself to allow the bricks to be thrown away. I claimed them as my own without any pushback from my brother or sister, and without much thought that I might be claiming more than just a couple of crumbling bricks. As I placed them on a bookshelf in my office I told myself someday I’d look into their history a bit more.

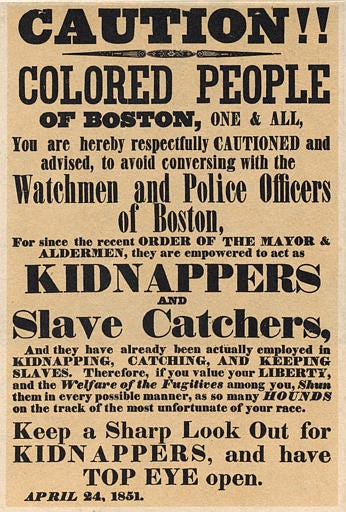

In late February of 2020, I visited the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park. As I took in the exhibits, I was slapped in the face with a hard truth. It was an old posting from Boston, the city I grew up near and where I developed a good part of my identity. It read:

CAUTION!! COLORED PEOPLE OF BOSTON, ONE & ALL, You are hereby respectfully CAUTIONED and advised, to avoid conversing with the Watchmen and Police Officers of Boston, For since the recent ORDER OF THE MAYOR & ALDERMAN, they are empowered to act as KIDNAPPERS AND Slave Catchers…

The message was clear. While owning slaves was unlawful in Boston, black people were still considered second-rate by many. Escaped slaves would be legally rounded up by police and sent back into captivity. It wasn’t a sign I wanted to see. I didn’t want my northern ancestors to have played any part in chattel slavery. I felt better casting that responsibility elsewhere.

I’d grown up in New England – even called Boston home – and had developed a sense of self-righteous pride being a northerner. I liked being on the right side of history when it came to the American Civil War and slavery. I learned the history written by the winners – which to me meant “us” – and I’d developed the tendency to look at the south as “them.” Not us. They had slaves, we did not. They lost the war, we won.

So, we’d tended to push aside any thoughts that our family had anything to do with owning slaves. Except it looked like my family did.

We had those bricks.

No Trespassing!

I returned to the car where Jean was waiting, and as we left for her home where she’d fill me in on the details of that branch of the family tree, I began to get the sense it would be a poor choice to let on that the source of my sudden interest in our family’s history was my curiosity about the family’s participation in slavery.

Or, maybe I was just a coward.

I’d prefer to say I was just being polite, but this wouldn’t be the first time I’d avoided a difficult conversation by “just being polite.”

We arrived back at her home. As I sat on her sofa, Jean entered her kitchen and we continued some small-talk. As she made me coffee and presented me with an unwrapped Twinkie placed neatly on a plate complete with a paper doily, she began to tell me more about family I’d never met. Starting with more recent years, she showed me pictures of family gatherings, and explained who everyone was in relation to me. We reminisced a bit about my grandma.

We spent an hour or so of looking at pictures of my distant family members, and even older pictures of my American ancestors. As the family history clocked ticked backwards, I did my best to show I was interested in what she was saying. It was all important to me but even more important to her. The smiles as she talked and the wistful look I could see in her eyes told me there was more than a little pride. Finally, we got to a point where I believed it was safe to interject an innocent question.

“Jean, did our ancestors ever own any slaves?”

She didn’t scowl, look at me sideways or even miss a beat. Her answer was quick, evidence it wasn’t something she avoided talking about. “Oh, yes, we know that one of our ancestors owned more than 90 slaves.”

“Really?” I replied. The number was shocking to me. Over 90 slaves.

When I began this little inquiry, I had a romantic notion that I might meet an ancestor of one of the enslaved people my family had owned. You know, if I could by some miracle find one.

But 90 enslaved people…

I’d learned by looking at our family tree over the years that historically speaking, family trees grow faster than we might think. I imagine that a group of 90 people would have offspring measuring in the thousands now.

Victoria, Virginia is a small town. It’s actually decreasing in size. Given the way families expand, and the size of the town, I had a hard time imagining there’d be any black people there who weren’t offspring of my family’s enslaved people.

When I departed Jean’s home, I wasn’t sure if I wanted more information. Alas, she promised me more information complete with census data and genealogical information. And, as southern hospitality rules dictate, I’d have to receive what she wanted to provide for me, which I did.

I took reams of paperwork home. There was a lot of information there. It was clear to me the history was meticulously collected and to be honest, I was in a bit over my head. Still, I was intent to find answers about the possibility that one of my ancestors owned 90 people.

Looking through the charts I found the reality of the situation was different than what I was told.

From what I could see, there were two ways of collecting census data for people in the south- Census Records and Slave Schedules. Census data included the names, ages, and genders of everyone in the home. Slave schedules included genders and ages. No names.

From what I could tell from the documents in front of me, my ancestor owned 8 people – not 90 – and most of them were children.

The answer to my question was staring up at me in black and white. “Yes.” Our family had enslaved people.

Sometimes I consider what I’d say if I ever met a descendent of an enslaved person my family owned. Part of me wants to apologize. I want to look them in the eye and say, “Hey, I’m sorry for the fact that my ancestors owned some of your ancestors.”

Sounds easy, right? Like, there isn’t a lot to lose by apologizing for something someone else did several generations ago. They might even look at me and say, “It’s ok, it’s not like you owned them yourself.”

I’ve had people say that to me. People who care about me and don’t want to see me carry around undue guilt and shame. I’m not sure I feel guilty, exactly. But I don’t like it. I can’t change the history. As Jean and I were discussing our family’s history, she tried to reassure me that our family would have been good to our enslaved people. She was sure they treated them like they were part of the family.

Those remarks don’t do a lot to make me feel better. The fact is, an enslaved person could not leave if they chose to. This is what being in bondage means. You may not leave, even if you so desire. This is what makes an escape from slavery, well, an escape.

It can be easy to have circular arguments about what it was like and so on. My friends can try to reassure me, and I can have my doubts.

So I pick up the brick and gently place my finger in the indentation. I consider the impression it left, and I continue my journey for answers.

Hey Jeff, I am not sure how I feel about the fact I have a 9th great grandfather Henry Kinne ( came as an indentured servant) that spoke against Rebecca Nurse, during the Salem witch trials. It was quite sobering! Another branch is attached to the Mayflower, which I was proud of, but these branches also purposely gave small pox to Native Americans, during the King Philips War. Yet, we were "evangelicals" back then trying to "convert the heathen" . I struggle with the knowledge that my ancestors were at the very least turning a blind eye to atrocities committed against human beings. All that to say I hear your dilemma.

Excellent story!