A Christian College Closes: Is Yours Next?

We Were All Connected

Tuesday I sent a message to an old friend who recently announced he was leaving his pastoral ministry role and beginning to take a new position as a hospice chaplain. I wanted to share a Substack with him, Hospice Matters by Larry Patten. Larry is a retired hospice chaplain sharing his wisdom and insights with anyone interested. I’ve been interested. I was sure my friend would appreciate it as well.

It had been three years since I messaged him about anything and likely twenty years since we’d been in the same room together. I was surprised by his response.

“Hey, it’s funny you should reach out as I almost texted you earlier today. You know anything about ENC?”

ENC is Eastern Nazarene College, our alma mater. I do, in fact, know some things about ENC. But I hadn’t heard any new scuttlebutt, so I wasn’t sure why he was asking.

“Context?” I replied.

“There’s grapes on the vine that maybe it’s about to announce its closure.”

Truth be told, there have been rumors about ENC closing its doors for decades. They were always rumors and were always squashed by people who knew better.

My wife sat on an advisory board for the college, mostly reluctantly. So, I thought we would have heard. She returned from the last meeting they had feeling better about the future of the college, which was different.

“I do not believe that is the case.” I replied.

But still…I wondered.

Sure enough, within a few hours the announcement was out. It was true.

What started as a text message to a friend about a hospice chaplaincy blog turned out to be how I’d learn about the death of my college.

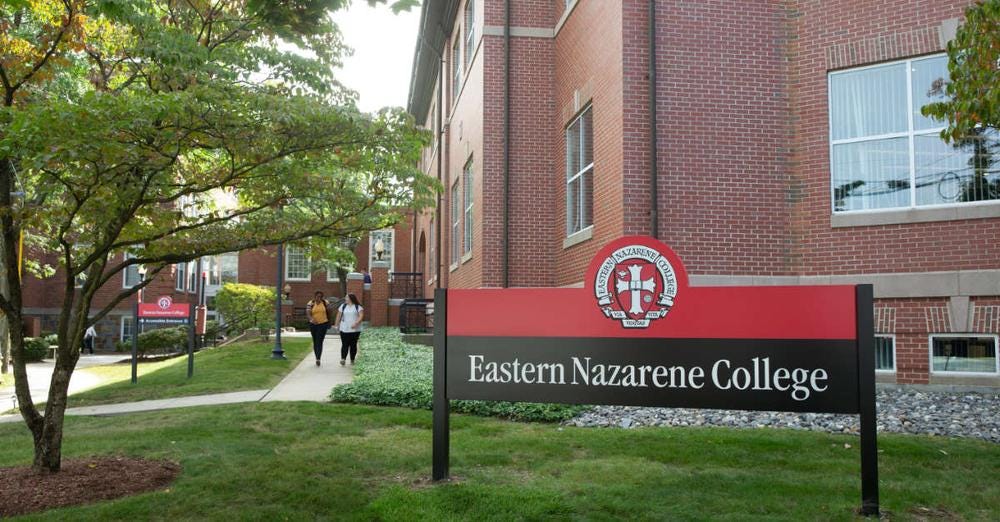

It would have been sad enough at that, but there was much more to it for me. As the evening progressed, I checked my Facebook feed. Friend after friend posted the link to the announcement. The picture you see above the article is the same one that adorned the statement with each post.

The building is the Nease Library, named after Floyd Wesley Nease, my maternal great-grandfather. He was the 2nd president of the school and died at the young age of 35 while on a fund-raising trip leaving behind a young wife and two small children, one of whom is my grandfather. Grandpa would follow in his father’s footsteps and eventually go on to serve as president of 4 institutions in the Nazarene denomination, the last of which was ENC from 1980-1989. College Historian James Cameron referred to the 1980s as “the good old days” when talking about Grandpa’s time at the helm. It was comfortable and convenient to be a white evangelical in the 1980s. This was particularly true for me as a son of a pastor and grandson of Nazarene royalty. Life was all roses, and the air in the bubble smelled like Ivory Spring.

So, my heart hurts today.1 Early in my adult life, not long after graduating from the school, a well-meaning administrator put the idea in my head that I could be President of ENC someday. I thought it was a call from God. Today, I believe it was an emotional, nostalgia-filled concept. Anyway, it didn’t happen. I don’t blame God anymore.

All this to say, when I heard the news on Tuesday, it seemed like a family legacy died. I loved the place. I have much gratitude for what ENC did for me. If you’re reading this in hopes of reminiscing with me, I feel you. It’s time for that.

But likely it would be better for you to stop reading here. Because what comes below is not a nostalgic reflection, but a critical look at how things have changed and why it's important to acknowledge the failure.

It’s a habit of mine.

This is Nothing New

ENC isn’t a unique experience in the world of Higher Education. According to The Hechinger Report, colleges are closing at a pace of one per week. Bestcolleges.com reports 60 colleges have closed since March of 2020. The math between the two reports seems off to me, but I was a Psychology major so what do I know? What I glean from a Google search for “college closings” is that my alma mater isn’t an outlier, and I admit this brings some emotional relief. Misery likes company.

COVID hit higher education hard, especially small, private institutions without large endowments. But much like the virus was hardest on those with pre-existing health problems, the pandemic was the death knell for colleges with pre-existing health problems. In fact, as I consider the past two-plus decades as a staff member and alum of ENC I wonder if COVID might have been a form of euthanasia. The closing isn’t a surprise. It was time. It was likely beyond time.

I spent most of my evening after the announcement reactions to the news as I scrolled through my Facebook feed. There were some themes. Most people are grateful for their time at the school. Nobody is particularly surprised and a few showed how frustrating the drawn-out process has been. Two posts seemed to sum it up well.

Complicated grief hits different.

This has been a long time coming and the news is no surprise – except perhaps how long the school lasted in hospice. [A coincidental analogy with mine.] It has been a slow-motion train wreck.

ENC has been toxic for years – done in by regressive/repressive policies and inept administration.

And yet – My years as a student were formative…

My friend went on to discuss her gratitude for the positive impact of professors and friends she had at the institution.

Another summarized what I believe gets to the heart of the issue.

ENC was, in my opinion, too liberal for the Nazarene Church and too conservative for the Northeast. Undoubtedly there were other poor choices and unfortunate circumstances, but to me their failure to be representative of their student body and their faculty is what ultimately shut the doors.

I might add the school failed to be representative of a significant portion of recent alumni as well. My own class (’98) had little interest in staying connected. This past fall we celebrated our 25th reunion. I was there with one other classmate and a visitor from another class who showed up to chat. We shared donuts for 30. The lackluster experience was something I’d predicted.2

While most of my newsfeed was full of grieving people reminiscing about the positive impact the school had on them during their time there, I also know there are people snickering in the wings. There are those who are likely saying something to the effect of, “Well, this is what happens when you go liberal. If they’d focused on their original calling and got back to the foundations of our faith without letting the culture affect them, things wouldn’t have come to this.”

On the other hand, there are those with the opinion that the evangelical [read: homophobic] campus couldn’t burn down fast enough.

In a world that is evolving, ultimately ENC could not, and it is a microcosm of a reality the Nazarene denomination is facing. ENC’s closure has as much to do with a denominational crisis of identity as it does with financial instability. It has been a house divided, and we know what happens to houses like that.

Try To Keep Up

When my grandfather was president at ENC he hired a young professor named Karl Giberson. Dr. Giberson was a physicist who would spend his years at ENC teaching in the science department. Standing in the chasm between scientific principles and fundamental Christian ideology became his life’s calling. He’s written numerous books on the subject, perhaps best illustrated by Saving Darwin: How to be a Christian and Believe in Evolution (HarperOne, 2008). For a time, he served as the Executive Vice-President of the BioLogos Foundation, an organization dedicated to the discussion of issues in science and theology.

But try as he might to bridge the gap, evolution theory was anathema for some in church leadership. The conservative fundamental influence on ENC was vocal in their displeasure of Giberson as well as other science professors’ influence on the minds of its students. There were rumors of large monetary gifts being withheld as long as Giberson was on staff.3 He departed ENC in 2010, leaving no doubt that the challenges he faced from fundamentalist Christians opposed to his work played a part in the decision.

My hunch is that there were some other issues as well, and the hunch comes from my personal experience with Karl.

I’d had the opportunity to sit in his classroom to complete part of my liberal arts core curriculum requirements. EMES (Epoch Making Events in Science) was my first brush with intellectual elitism. Though with reflection I have to admit it really wasn’t really elitism so much as it became clear that there are college kids - like me - and then there are college students - like the ones who understood the importance of studying, how to do it and know how to get A’s in difficult classes. EMES was difficult. I earned a C…I think.

But you’ll note I’ve switched from referring to him as “Giberson,” to Karl. I grew to know him a bit outside the classroom. He was also my girlfriend-turned-wife’s academic advisor. Upon graduation my wife began working for his wife who was the college registrar. We’d spend some time with them and I’d get to know Karl a bit. I regard him as a friend today, and I think he’d be OK with that.

Karl was academically intimidating for me; I just couldn’t keep up with his mind. Sometimes I’m not sure he understood this, which I think is something brilliant people often struggle with. They’d like for us to catch up, and when we don’t everyone is frustrated.4

Karl’s frustration with ENC wasn’t just about evolution and the church’s resistance to it. The various leaders that graced the offices of the administration building through the years were limited in how they could operate. Whereas the founders of the institution were able to subsist on little and sacrifice much, the cost of living in the Boston area combined with the amount of work required for professors to maintain academic standing in various disciplines outpaced ENC’s church-led growth and administrative capacity. Professors or professionals who wanted to have an impact in their discipline couldn’t stay at ENC because it was neither economically feasible or professionally viable. They’d get a start, build somewhat of a resume, and leave. Or, in the case of the religion department, it would grow “too catholic,” they’d see things “restructured” away from anything that would challenge status quo doctrine.

The situation was untenable.

When I worked at ENC in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a new, young religion professor named Thomas Jay Oord. We attended the same church and played basketball together. In the short time he was at ENC, he became a well-loved professor and colleague. To have rubbed elbows with minds like Karl and Tom is one of my most cherished experiences. He’d eventually leave to teach at a sister school, Northwest Nazarene University, and it was a loss felt by all, even after only a short time.

These days, Tom is one of the voices fighting for the Nazarene Church to accept an affirming position for queer people. As a result, he will be standing trial within the church for teaching doctrines contrary to that of the denomination. His credentials as a minister are at risk. It’s not a small thing. Where some brave people are fighting behind the scenes, Tom is pushing the issue in as vocal of a manner as he possibly can.

Not long ago Oord published a book, Faith After Deconstruction, with author, host of the Homebrewed Christianity Podcast, and recent Substacker, Tripp Fuller. For people like me who have taken to a new understanding of Christianity, people like Oord and Giberson are a lifeline when it comes to being authentic in my Christian faith, willing to let our doubt lead to discovery rather than to the fear of burning in hell.5

Where Giberson was challenged by the church folk from a non-scientific perspective, Oord faces reprimand for his insistence that the denomination is wrong in its doctrine regarding queer people. His battle isn’t at ENC. In fact it’s in a different corner of the country, but as far as the Church of the Nazarene goes, it might as well be in the pew across the aisle.

For far too many in our denomination, fear of offending God in the face of scientific realities combine with homophobia to stand in the way of authentic human progress. For ENC, an evangelical Christian institution founded at the turn of the 20th century, trying to thrive in the academically rigorous environment where Harvard and MIT lead the way in academic thought, it became difficult to understand just who it was serving. Was it the conservative church which founded it at the turn of the 20th century, or the modern, college-bound high-schoolers of the region?

The ENC family is fond of quoting our first Academic Dean, Bertha Munro. “There is no conflict between the best in education and the best in Christian faith.” But proving this to be true has been more difficult than we might be willing to admit.

Education involves learning new things. Even if it means challenging what we once knew to be true.

A Closing Thought

I’m part of the ENC family. I’m still proud to be, class reunions notwithstanding. I wish it hadn’t come to closure. But foundational to our Christian faith is the idea of death and resurrection. Death gives way to life. And when the life is renewed, it looks altogether different and better, more impactful than before. This is how it goes.

The announcement of the plan for closure stated that, “transitioning to a new educational enterprise is the only viable path for continuing ENC’s mission of providing transformational education.” I hope it’s not a platitude. I hope that the death of what was provides opportunity to transform into something which will allow for progress in the future.

We shall see.

Here are the earlier articles referenced in this post:

My story is not unique to the Nazarene world. The leadership is family-driven, or was for some time. Many have great pride in the depth of their generational ties to the denomination. ENC has many people whose stories of familial ties mirror my own.

At the time I posted the linked article I was still in the habit of posting my articles to Facebook, and the Facebook algorithm wasn’t limiting who saw them yet. It became my second-most read piece, and I gained a handful of subscribers. I didn’t expect those things to happen, but it was indicative of agreement on a gloomy outlook.f

They were also vocal in their pleasure when he left, and it appears these rumors were unfounded, as the gifts never materialized.

While my EMES experience was somewhat academically traumatic (and the face of my imposter syndrome may sport a mustache, curly-ish hair and glasses), his influence on my life and scores of other ENC students is profound. His mentorship and guidance have shaped countless careers and lives, including my wife’s and mine, in ways that extend far beyond the classroom.

I’ve met Tripp Fuller, though only briefly. He’s another brilliant mind I can’t always keep up with. As I watched him give a talk once, it was as if I could actually see the neurons firing in his brain at lightning speed. Intimidating? Um, yes. At least when it comes to intellect.

Your point about professors unable to stay long term because of the academic requirements and the cost of living really stands out to me. It seemed to me that the professors I with whom I spent the most time were serving sacrificially in their roles at the college. Certainly many of them could have taught in many other more prestigious institutions for more money. I believe the education I got at ENC was rigorous and worthwhile. I am infinitely grateful to those professors who gave of themselves for the mission of the school and their love for the students. Shetler, Millican, Brandes, Yerxa, McCormick, Giberson, Cameron(s), the list goes on.

Thanks for this reflection. I’m thankful that the Google algorithm brought me here.

I graduated five years before you. ENC prepared me well academically. I went on to get a PhD in the sciences and, after that, a law degree. I’m now a corporate attorney at a tech company in the NYC area. It was probably the right place for me at that time. But my experience felt somewhat provincial within a few months after leaving campus. Even by the mid-1990s, it seemed like ENC was trying to embody a worldview that was fading away. It didn’t fit comfortably into the politically right-wing mega-church culture that was coming to define evangelicalism and, in particular, the Nazarene church. And it didn’t fit comfortably into the increasingly secular culture of the Northeast.

I loved my four years at ENC and have few regrets about my choice to attend. When I graduated in 1993, I imagined that I would return frequently. But I didn’t. In fact, I didn’t go back until my 25th class reunion in 2018. I couldn’t explain why I stayed away for so long. But I think it had something to do with the fact that ENC represented a culture—namely, that of left-leaning evangelicalism—that never found its place among the cultural divides that began to emerge more sharply in the late 1990s. It probably also had something to do with the fact that the denominational leadership seemed to be pushing ENC towards a different side of those cultural battles than the side towards which I found myself moving.

I could probably say the same for the Nazarene church in which I was raised. Its theology and practice today have lost the imprint of theologians like Orton Wiley and Mildred Bangs Wynkoop. Most Nazarene churches today are barely different from fundamentalist mega-churches from the Baptist tradition. It seemed like the denominational leadership was seeking to push ENC in that direction. But that wasn’t workable in New England, where such churches are scarce. So, ENC found itself pulled to a different side of the culture wars from the side with which its prospective students and recent alumni in the Northeast had become affiliated, however loosely.

I also attended the reunion weekend this past fall, and attended the inauguration of the new President. It was a disheartening experience. I felt like I was observing a kind of institutional suicide. In a strange way, ENC’s closure comforts me because I suspect that I would feel increasingly estranged from what the school would have become had the new vision for the school succeeded. It’s probably better that the school close with a modicum of its former legacy intact than have that legacy further trampled upon by those who would like to erase that legacy from its history.

ENC died because the world it served—the world of a more socially progressive evangelicalism—had died a quarter century earlier. Its integrity did not remain entirely intact, as evidenced by Karl’s departure and other events over the last two decades. But the effort to force ENC to embody the image of right-wing fundamentalist evangelicalism ultimately failed. By 2024, the choice for ENC lay between closing or becoming something grotesque. I’m glad that closure won out.